Improve Performance with the Object Pool Design Pattern in JavaScript

The Object Pool design pattern is used in order to improve performance. It does that by reducing runtime memory allocation and garbage collection.

Memory allocation and garbage collection performance implications

Memory is a resource every software is using. JavaScript code requires memory in order to store a lot of things. During runtime, memory allocation is mostly done for variables.

When you create a variable in JavaScript, a place for this variable is found in memory and then the variable points to the memory address found. When you create an integer, the JavaScript runtime will require a really small piece of memory. If you create an array of 1000 integers, it will require roughly 1000 times more space in memory.

Memory is released by removing all variables pointing to the same address in memory:

intArray and array2 point to the same address in memory. This is why changes to intArray members will also reflect in array2 and vice versa. To mark the array for removal the array completely from memory we need to remove the two references to it:

The variables we create and discard, like the array in our example, are marked for removal by a process called Garbage Collection (GC). The GC is a periodical process. It runs over all the stuff we put in memory and marks them for sweeping if they are not referenced anymore. Then, internally, it decides when to get rid of the marked memory pieces.

This might sound cool, cause JavaScript is taking care of us, but in some applications, this might have a price.

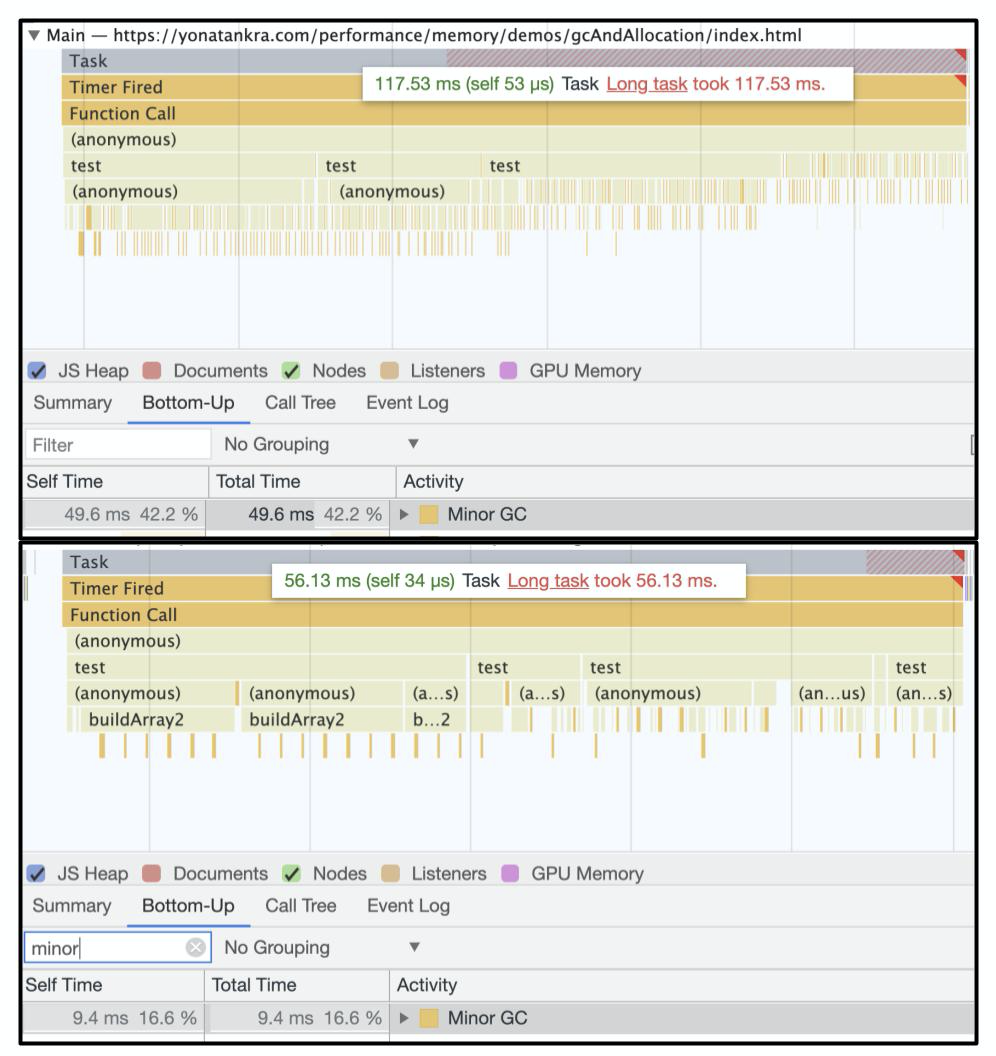

Figure 1: Recording of an application with garbage collection

In Figure 1, we can see a recording in which Minor GC took around 42% of the function call's runtime (bottom of the figure). In the flame chart at the top of the figure we can see a lot of yellow stripes at the bottom of the chart - these are a lot of Minor GC happening.

GC has its price - and one can unknowingly cause a lot of GC cycles that lead to one's application to slow down significantly. According to Murphy's law, this will happen at the worst time possible...

How to reduce memory allocation and garbage collection

As we've learned so far, GC is invoked when there are objects in memory that your JavaScript code doesn't have a reference to - just like our array in code snippet 3. The fact that our code is initiating a lot of GC cycles means we are also allocating a lot of memory. We solve these problems by preallocating memory.

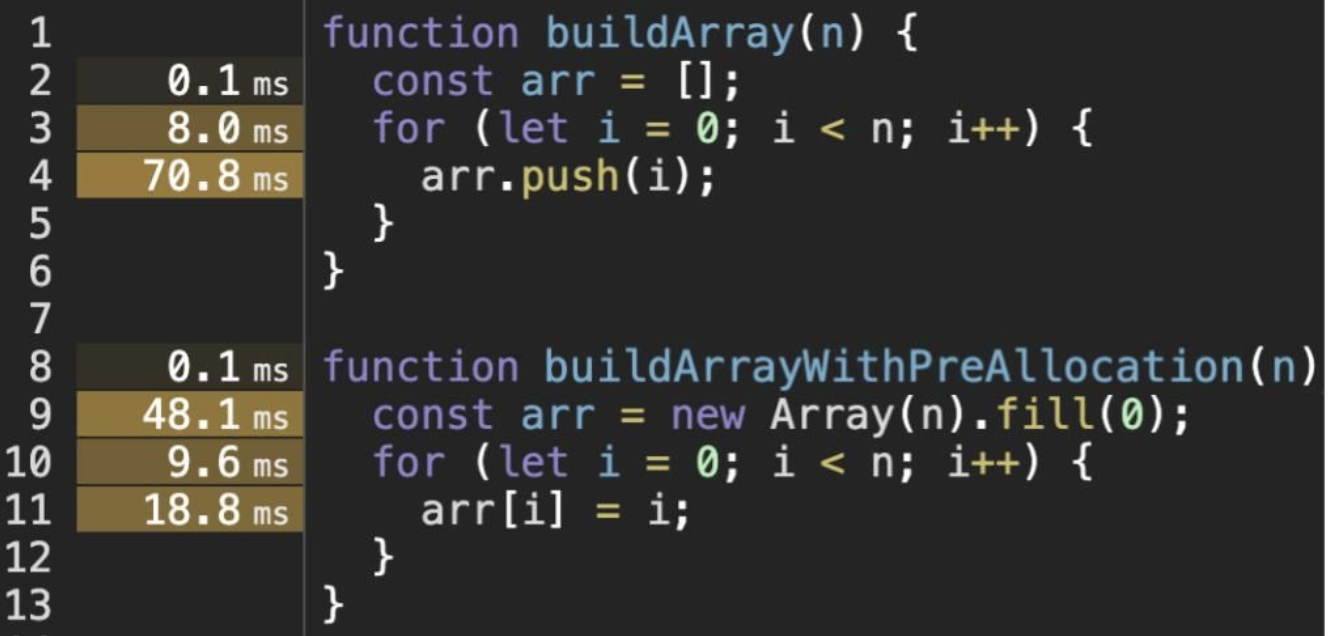

In code snippet 4, we have two functions. The first, buildArray, is a function that does something we do daily - push elements into an array. buildArrayWithPreAllocation, on the other hand, first creates an array of size n and then changes the values. The difference in measurement between these two functions will further illustrate the problem of memory allocation and GC.

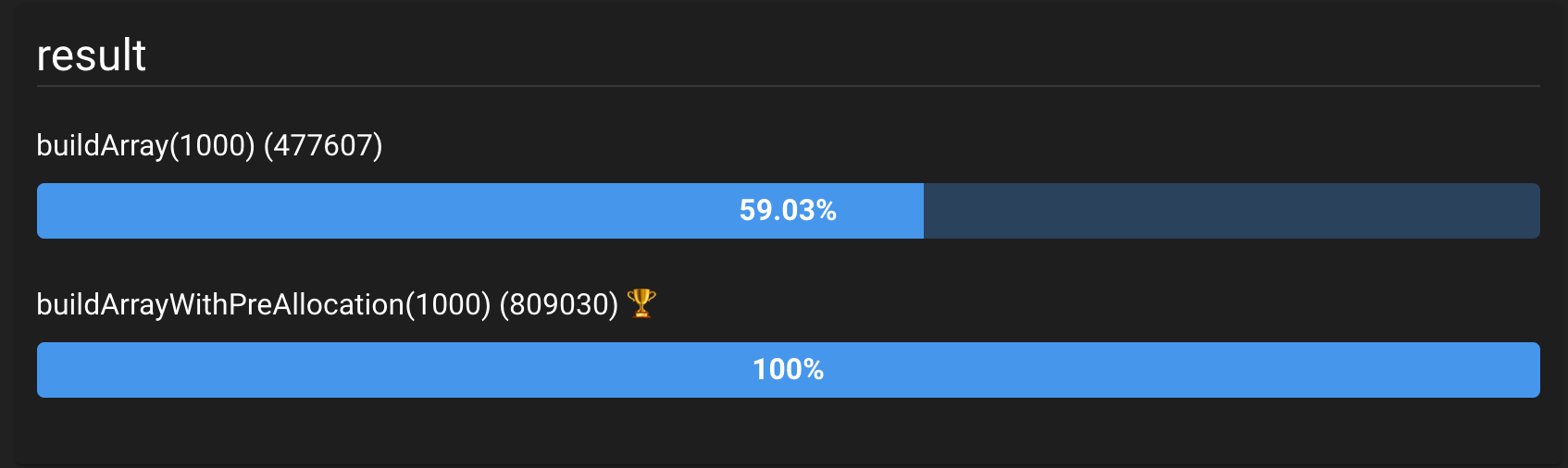

The benchmark of these two functions is shown in Figure 2. The benchmark tested how many times each function could be ran in 10 seconds. It can be seen that building the array with pre allocation was roughly 40% faster than pushing the elements one by one, hence it could run more times in that time period (buildArray ran 477607 times vs. 809030 for the pre allocation function).

Figure 2: Benchmark comparison of buildArray vs. buildArrayWithPreAllocation . buildArray was around 40% slower. You can run the benchmark here: https://jsben.ch/VNo6e

The following profiles demonstrate the causes of this time difference:

Figure 3: Top: Profiling results of buildArray. 49.6% of the time was spent on GC. The time it took the function to run was 117.54ms. Bottom: Profiling results of the buildArrayWithPreAllocation (called buildArray2 in the profile). GC was 16.6% of the runtime and it took the function only 56.13ms to run.

In figure 3 the sum of Minor GC is shown both for the buildArray (top) as well as the buildArrayWithPreAllocation (bottom). The bottom-left cell shows the amount of time spent on GC went down from around 50ms to 10ms. That's a 40 ms difference for the same task. We still have some time missing though. 117 - 56 is more than 40...

The rest of the difference can be attributed mostly to memory allocation. Memory allocation is also a time consuming process. The engine that's running our code needs to look for a place in memory for the new array elements and copy the array members to a new location in memory.

Using this simple preallocation technique reduced our GC and memory allocation by a huge factor.

This came with a price though. Preallocating memory increased our app startup time. This has to be taken into account when preallocating vs. dynamically allocating. Figure 4 shows the time it took to run each part of the functions. It can be seen in line 9 that pre allocation took almost 50ms. It paid off inside the for loop. If you sum up the times, you'll get to roughly the same number. That's because GC is measured outside the functions in Figure 4.

Figure 4: Time spent in each part of the two functions. Preallocation took almost 50ms, but was less costly in regards to memory allocation inside the loop.

Another caveat is that the preallocated memory is there for good. We have no mechanism of clearing up the preallocated memory. Once we've created the array - it is there for good, weather we use it or not.

One last drawback is that we need to know beforehand how many members the array needs. If we create it too small, we will hit the ceiling and cause more allocations and GC. If we set it too large, we just waste memory.

The object pool pattern solves some of these problems. It allows us to enjoy the benefits of preallocation with less caveats.

How to use an object pool to reduce memory allocation and garbage collection

The secret behind Object Pool is preallocation. Pre allocation of memory saves us both on GC and memory allocation. Lets implement an object pool and see how it overcomes the problems we mentioned with the simple preallocation (and what new problems it presents).

For this, we will build our ObjectPool class. The first thing we need is an array preallocated with anything we want:

The constructorFunction can be any function that returns a value. For meaningful usage, it would usually instantiate a class or create an object and return it.

getElement and releaseElement

Now that we have our preallocated array, we need a way to do two things:

- Get a free element of the array.

- Release an element of the array once we are done using it

There are many ways to do that. I will implement it by wrapping the actual object with our own ObjectPoolElement class:

We will also need a resetFunction so we could always return fresh data to our users. We can now use our new wrapper to implement the getElement and releaseElement methods:

In code snippet 7 we've added a few things.

The first is the resetFunction. We also set it on the class itself because we'd like to use it when we release an element (see the change in the releaseElement method). We also add the constructorFunction function to our class's methods.

Another addition to the ObjectPool class is the method createElement . This method returns an ObjectPoolElement that wraps a fresh data object. We use it in our initial array allocation.

Finally, we have our getElement an releaseElement methods. getElement looks for the first available (free) element. releaseElement receives an element object, sets it as free and resets its data

We now have our very basic object pool!

We can use it like that:

What happens when we run out of elements?

There might be a case in which we've set our initial size to n and we need n+1 or more elements. The naive way to do that would be to just push another element once we request an object and there's no free object:

In code snippet 9, we did 2 things:

- We added the

constructorFunctionto our class. - In

getElement, if we did not find a free element, we create a new element, add it to the pool array and return it to the user.

The getElement method, as it is now, has two optimizations we can apply on.

How to optimize an object pool?

Optimizing pool size

As discussed before, one of the drawbacks of a simple memory preallocation is the size of the preallocated array. With the object pool, there are several possible strategies to solve this issue. They all revolve about heuristics regarding the pool's size.

One such heuristic is to set a minimum free limit. For instance, decide that the pool must have at least 10% of its elements free. If this limit is reached, we double the size of the pool.

This way, we commence a "dynamic preallocation". It's much better than to push 5000 elements just when you need them most (probably when the user is waiting for some response).

The goes with reducing the size of the pool. Set a border from the bottom to decrease the size of the pool. If we have 90% free objects, we can reduce the size of the pool by half and save memory for our software.

Optimizing a new element lookup

Another thing that can be clearly optimized is the lookup for a free element. It has a complexity of O(n). This means that every time we want to fetch a new object, the worst case is that our search algorithm will loop over all the elements in our pool.

That could have been bearable, because running a loop over 5000 elements doesn't take much time. Remember that an object pool is meant to deal with rapid Create and Delete processes that initiate a lot of memory allocation and GC. That means, the getElement method will be used a lot and the for loop will run many times. Moreover - an object pool might hold much more than 5000 elements...

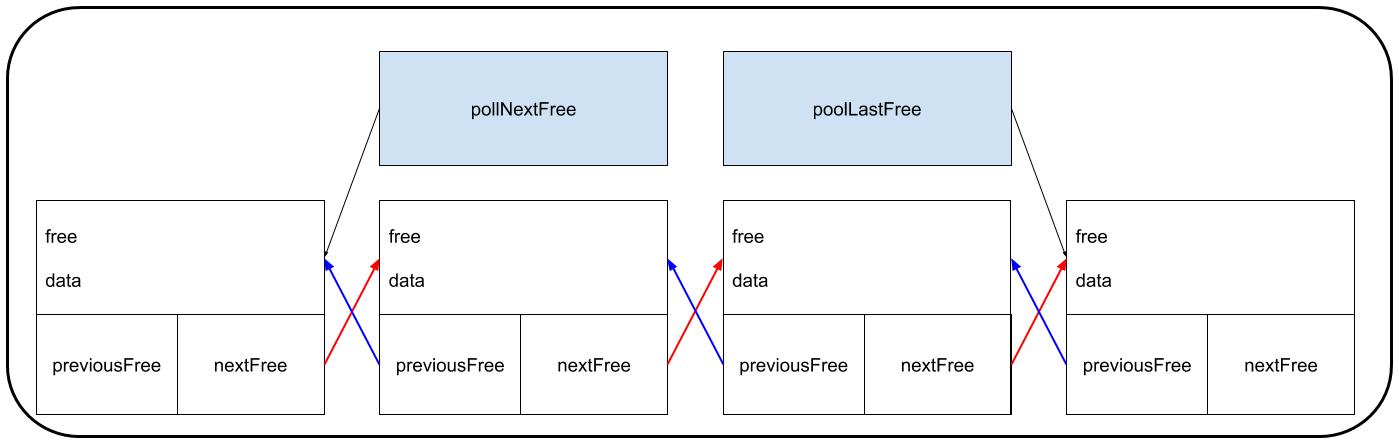

A possible solution to this problem is by using a linked list. More accurately, we will be using a doubly linked list (a.k.a. dequeue).

For every ObjectPoolElement we will have a reference to the next and previous free elements:

Figure 5: A doubly linked list of ObjectPoolElements. The element in the middle can be a lot of elements. Only the first and last have null links (previous and next respectively.

The ObjectPool itself will remember the first and last objects in that list. When a getElement request is made, the object pool just returns the first free object and replaces the reference to the first free object to the returned object's next.

When a releaseElement request is made, the poolLastFree is replaced with the newest released element and the former poolLastFree now points to the newest released element as its nextFree.

This way, every request for a new element takes constant time.

This can also be done without the dequeue. In the code snippet below you can find two full examples with both optimizations in place. One example uses a dequeue and the other saves the currently free index.

1: Object Pool No Linked List

2: Object Pool

When to use an object pool

There are various real life examples to object pool usage. Game engines are using them, obviously. A library many nodejs developers use also has a pool in action:

https://github.com/petkaantonov/bluebird/blob/master/src/queue.js

It uses pooling techniques to increase and decrease the queue size and uses the dequeue data structure to optimize.

The main concept behind an object pool - preallocation - can be used on its own. If you have a loop that's creating a new array and running a lot of times you'd might not need a pool - just pre allocate the array before the loop.

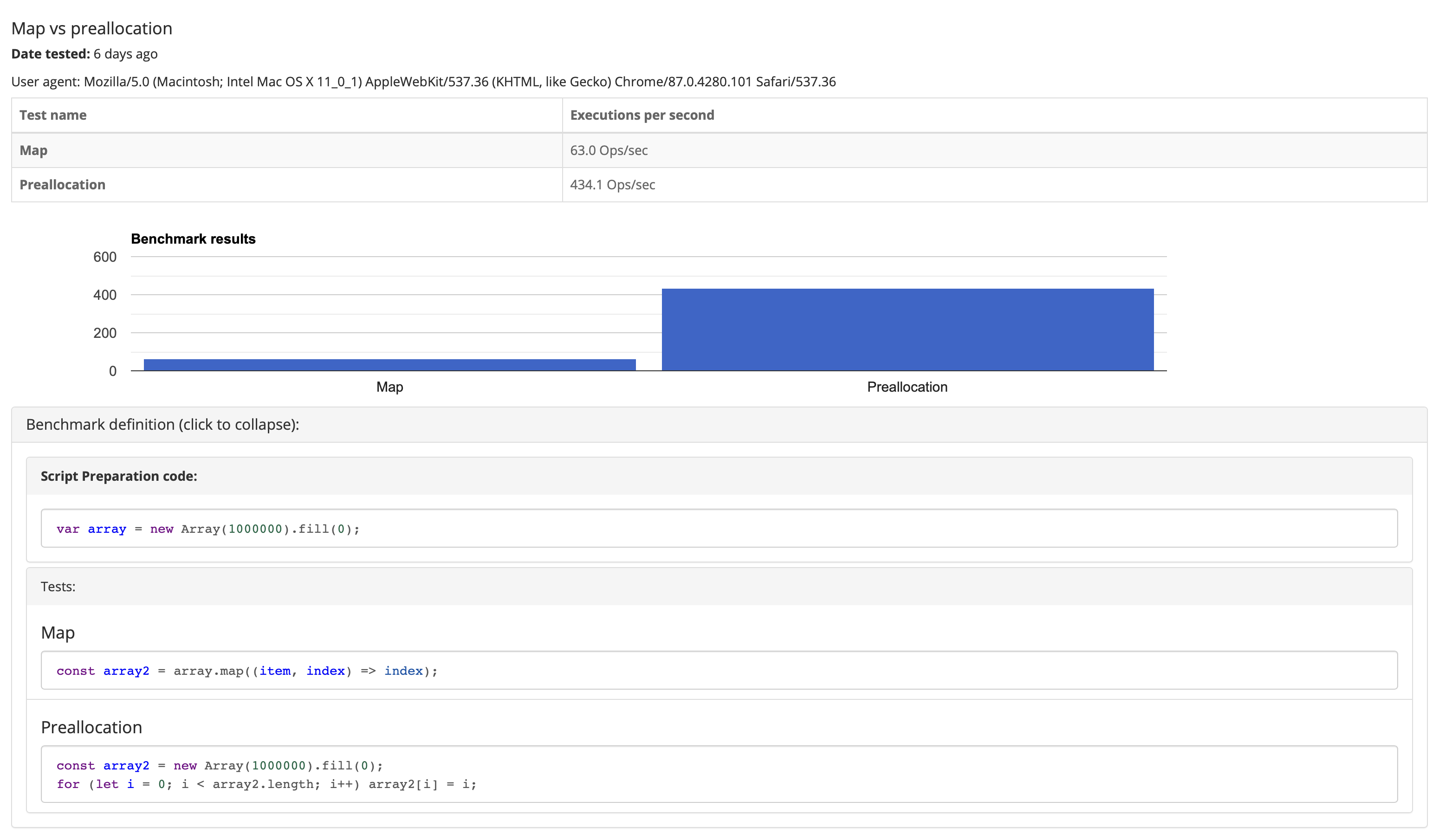

For instance, you'd might want to replace a map of a big array with a for loop with pre allocation. When comparing:

With:

https://measurethat.net/Embed?id=154869

An object is handy when you need to allocate a lot of objects of the same type from various areas of your application - much like getting data from a server.

Summary

In this article we've learned about the price we pay for memory allocation and garbage collection. They both can keep our main thread occupied while other important tasks are taking longer to run.

We saw we can preallocate memory we pay this price in a known less critical time. This allows us to free the main thread while critical tasks like handling an API request or running animation in the browser are supposed to run.

While preallocation can have performance benefits, it can be good to mainly handle performance critical loops when you know the size of the array you need beforehand. When you need an application-wide optimization, with rapid creation and deletion of elements - the object pool design pattern come into play.

I hope you enjoyed this article and learned a thing or two about Javascript runtime optimization while at it.